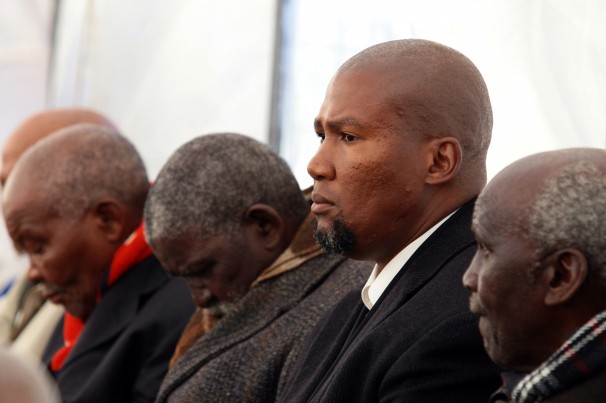

Mandla Mandela, center, grandson of former South African president Nelson Mandela, sits with the elders of Qunu during the funeral of his relative 97-year-old Florence Mandela on June 15, 2013 in Qunu. Nelson Mandela's family sought criminal charges of grave tampering against the former South African president's oldest grandson on July 2, 2013, amid an escalating row linked to the eventual.

It seems like a storyline from a lurid soap opera. The remains of an aging patriarch’s three deceased children are secretly moved from their graves in a family plot. Years later, other family members go to court to have the bodies returned. The messy fight — over legacy, money, and traditions — unfolds as the patriarch lies critically ill, unable to intervene.

Only this is not fiction, and the patriarch is Nelson Mandela.

As the anti-apartheid icon fights for survival in a hospital, his family is clashing over where and how he is to be buried. The squabble is playing out in newspapers, online and on TV, angering a nation gripped with grief and praying collectively for their beloved 94-year-old former president to remain with them longer.

The family feud is precisely the sort of drama Mandela had sought to avoid in his later years. He had withdrawn from public life to Qunu, a remote village where he grew up, eager to spend his last days in peace.

“It’s a disgrace,” said Edward Kutoane, 37, a security guard who was playing with his toddler son steps away from Mandela’s old house, now a museum. “It violates the very principles the old man lived by. He lived a peaceful life with respect for others. We expected his children and grandchildren to be the same, but they have forgotten where they come from.”

The fight over the graves is the latest chapter in a family saga over Mandela’s legacy and what he passes on. In recent months, two of his daughters have sued to gain control of companies set up by a Mandela trust that is reportedly worth millions of dollars, while other relatives have marketed Mandela’s name and image in other commercial ventures, even in a television reality show called “Being Mandela.”

A South African high court judge last week ruled that a group of 16 relatives and senior clan members of Mandela could exhume the remains of his three children and return them to Qunu. The plot there includes a grave prepared for Mandela, who has expressed that he wanted to be buried next to his children.

But Mandla Mandela, his eldest grandson, is contesting the court ruling. In 2011, he allegedly moved the remains to his home in Mvezo, a village about 14 miles from Qunu. Mwezo is where Nelson Mandela was born. Neither the family nor the elders of Mandela’s clan were consulted. The remains in question include Makaziwe, Mandela’s first daughter who died when she was nine months old; Thembekile, who was killed in a 1969 car accident; and Makgatho, Mandla’s father, who died of an AIDS-related illness in 2005.

The family fight grew more tense this week. Reports emerged that Mandela’s relatives have lodged a criminal complaint against Mandla, accusing him of illegal grave tampering.

Where Mandela is buried could determine who will lead Mandela’s family after his death. Mandla, who is the oldest male heir, is the local tribal chief of Mwezo as well as a lawmaker with the ruling African National Congress. Mandela’s daughter Makaziwe, who was given the same name as her deceased sister and is the elder of his surviving children, is widely seen as a leader of the family. In recent months, she has appeared more outspoken, giving interviews about her father’s condition and criticizing foreign media’s handling of the story.